Toy

Toy (2020)

Exhibited

2020

Chad McCail, Northern Gallery of Contemporary Art, Sunderland

Notes

In Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism, David McNally writes that the monstrous nature of capital is invisible simply because it is so ubiquitous. He argues,” that critical theory must be capable of developing a dialectical optics, ways of seeing the unseen…and this means that invisible powers- market forces - are, at the same time, fundamentally real. Market forces constitute horrifying aspects of a strange and bewildering world which represents itself as normal, natural and unchangeable. For this reason fantastic genres, be they literary or folkloric, can occasionally carry a disruptive, critical charge, offering a kind of grotesque realism that mirrors the absurdity of capitalist modernity the better to oppose it.” Note 1

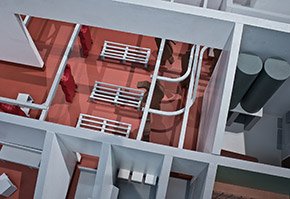

In Toy everything is made from cardboard and wood, insulation foam and papier-mâché. The production values are those of a community play and the hand is evident not to indicate the individuality of the artist but to convey that the urgency of the story has not permitted refinement. It does not seek to seduce with a slick, machined sensuality but rather it appeals to the childish pleasure in toy layouts where scales clash and a fantastic but coherent reality is constructed from diverse elements.

In appealing to the child’s vision it aims to recall to the viewer something of the young persons early, emotional responses to the world, something of its expectation of acceptance and affirmation, that it will be treated with warmth and kindness, that adults are generally co-operative and are working together for the general well-being of all.

In attempting to invoke this sense in the viewer it aims to awaken a sensibility which disposes the viewer to identify with the struggle of the people and invoke their shock and horror at the behaviour of the cash register-headed monsters.

The magnitude of the horrifying forces of the free-market can only be combatted by combined action. The peoples’ mutual opposition, their communal strength and unity of purpose has released hidden reserves of courage and resilience. Just as the determining forces of the free-market are visible in Toy, so the potential energies of solidarity and cooperative action are also apparent.

A great figure composed of hundreds of individuals feeds a banking monster into the jaws of a great snake. Invoked by the people’s respect for the plants and animals it digest the banker and shits him out again but reduced to normal size.

The peoples’ powerful desire for a way of life which will honour the animals has led them to abandon the mechanised slaughter of the abattoir and called forth a horned god, the ancient memory of a time when there existed an empathy for the beasts they hunted.

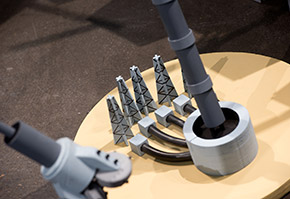

At the military base a transport plane has returned to pick up new tanks for the war for oil. Death, the product of war and its conscripted spirit, emerges from the rear with the coffins of dead soldiers. Released from service to the global arms industry by the insurgent action of the tank-factory workers it turns on its abusers.

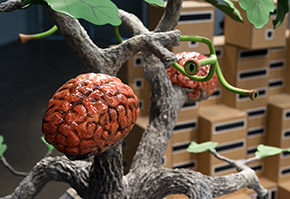

The ancient tree of knowledge, intelligent, observant and sexually fertile, has burst through the roof of the church. A branch reaches up to grasp the testicles of the deflated male sky god. Its roots extend outward, bursting through the concrete to seize and consume those possessed by the craving for personal accumulation. Like the great snake the tree has the power to bring the giants down to size and they emerge reduced and humbled from the fruits of the tree which the serpent, freed form the gods curse and standing erect again, passes to the children outside the empty school.

In Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, Maya Deren sees the primary function of Voudoun rites and practices as imbuing and instilling in the participant the principle of collective action and eliciting from him or her a positive contribution to the community. She sees the principle of participation at the core of collective religions. Note 2 .The gods themselves, like Robert L. Moore’s archetypes, are amoral. They are the powerful desires with which a person must become acquainted and learn to honour if he or she is not to be possessed and overwhelmed by them. Initiation does not involve repression or the denial of desire but a process of familiarisation within the protective shelter provided by rituals involving the community.

The people are not driven to seek revenge. The residents of the housing estate are digging up the roads and planting vegetables and fruit trees. Their attitude towards those whose humiliation has been complete is compassionate and forgiving. Instead they are considering what they will keep and what they will reject of the industrial world which gave birth to such monsters.

Note 1: David McNally, Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism (Chicago, 2012),6-7

Note 2: Maya Deren, Divine Horsemen:The Living Gods of Haiti (New York, 2004), 191-2