Compulsory Education

Compulsory Education (2008)

96 x 140cm, screenprint, edition size 20

Exhibited

2008

Chad McCail, Edinburgh Printmakers

2011

Rotate Laurent Delaye Gallery

Compulsory Education (2009)

2.3 x 60m, oil on boards

Exhibited

2009

Systemic, NGCA, Sunderland

2016

Cupar Arts Festival

Notes for Compulsory Education

My principal source for Compulsory Education is John Taylor Gatto’s The Underground History of American Education, New York, 2006.

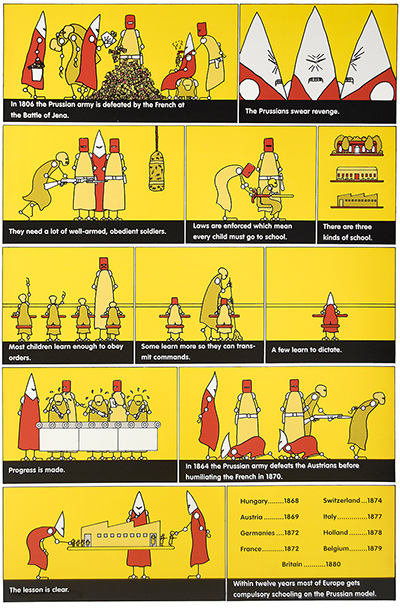

In the chapter entitled The Prussian Connection, Gatto traces the origins of mass compulsory education in nineteenth century Prussia.

Following the Prussian defeat by Napoleon at Jena in 1806, the philosopher Johann Fichte made a series of lectures known as the Addresses to the German Nation.

“In no uncertain terms Fichte told Prussia the party was over. Children would have to be disciplined through a new form of universal conditioning. They could no longer be trusted to their parents. Look what Napoleon had done by banishing sentiment in the interests of nationalism. Through forced schooling, everyone would learn that "work makes free," and working for the State, even laying down one’s life to its commands, was the greatest freedom of all.1

Fichte’s address initiated a debate in Prussia which lasted until 1819 when a new model of mass schooling was implemented.

“The Prussian mind, which carried the day, held a clear idea of what centralized schooling should deliver: 1) Obedient soldiers to the army; 2) Obedient workers for mines, factories, and farms; 3) Well-subordinated civil servants, trained in their function; 4) Well-subordinated clerks for industry; 5) Citizens who thought alike on most issues; 6) National uniformity in thought, word, and deed.2

This system provided three different levels of schooling,

“At the top, one-half of 1 percent of the students attended Akadamiensschulen, where, as future policy makers, they learned to think strategically, contextually, in wholes; they learned complex processes, and useful knowledge, studied history, wrote copiously, argued often, read deeply, and mastered tasks of command.

The next level, Realsschulen, was intended mostly as a manufactory for the professional proletariat of engineers, architects, doctors, lawyers, career civil servants, and such other assistants as policy thinkers at times would require. From 5 to 7.5 percent of all students attended these "real schools," learning in a superficial fashion how to think in context, but mostly learning how to manage materials, men, and situations—to be problem solvers. This group would also staff the various policing functions of the state, bringing order to the domain. Finally, at the bottom of the pile, a group between 92 and 94 percent of the population attended "people’s schools" where they learned obedience, cooperation and correct attitudes, along with rudiments of literacy and official state myths of history.”3

The Prussian elite was aware of the dangers of a literate working class and after thorough study they adopted the ideas of the Swiss educational reformer Heinrich Pestalozzi who claimed the ability to mould the poor “to accept all the efforts of their class”4. Gatto calls Pestalozzi’s system,” a non-literary, experience based pedagogy strong in music and the industrial arts”5.

Prussian schooling was widely admired. A thorough report by Victor Cousin to the French gov’t in 1831 dwelt,

“at length on the system of people’s schools and its far-reaching implications for the economy and social order. Cousin’s essay applauded Prussia for discovering ways to contain the danger of a frightening new social phenomenon, the industrial proletariat. So convincing was his presentation that within two years of its publication, French national schooling was drastically reorganized to meet Prussian Volksschulen standards.”6

Gatto concludes,

“When the spirit of Prussian pelotonfeuer crushed France in the lightning war of 1871, the world’s attention focused intently on this hypnotic, utopian place. What could be seen to happen there was an impressive demonstration that endless production flowed from a Baconian liaison between government, the academic mind, and industry. Credit for Prussian success was widely attributed to its form of schooling.“7

Europe followed quickly.

“For the enlightened classes, popular education after Prussia became a sacred cause, one meriting crusading zeal. In 1868, Hungary announced compulsion schooling; in 1869, Austria; in 1872, the famous Prussian system was nationalized to all the Germanies; 1874, Switzerland; 1877, Italy; 1878, Holland; 1879, Belgium. Between 1878 and 1882, it became France’s turn. School was made compulsory for British children in 1880.”8

How far the introduction of this form of schooling in discipline and obedience was responsible for the acquiescence of vast numbers of people to the nightmare of trench warfare is a question Gatto leaves aside.

References

1 John Taylor Gatto, The Underground History of American Education, (2006), p 132

2 ibid, p132

3 ibid, p137

4 ibid, p138

5 ibid, p138

6 ibid, p139

7 ibid, p140-1

8 ibid, p142

Gatto’s book is available free online at:

https://lvassembly.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/underground-history-of-america-education.pdf